Winter 2013, Issue #70: Editor’s Note

Dear Readers,

Dear Readers,

During recent travels through the Himalayan mountains of Nepal, I spent time in Tamang villages accessible only by four days of walking into the Langtang River valley. Tracing their ancestry from Tibet, for 1000 years or more, these indigenous inhabitants of Nepal have resided along the Tibetan border, often at elevations of 12,500 feet and above.

The daily lives of these strong people revolve around satisfying basic needs. Plots of buckwheat, millet, barley, potatoes, cabbage, cauliflower, and other greens are tended. Cow or dzo (a cross between a cow and yak) dung is collected into large baskets, strapped to the back of a man or woman, then carried to the fields. Rows of dome-shaped piles of manure line the field where these baskets have been carefully turned upside down and emptied, adding fertility to the fields. Laundry and dishes are washed by hand under hoses of cold water piped from the Langtang River, or one of its tributaries. Firewood is harvested with sharp machetes, then carried home on the backs of villagers. Yaks are milked, eggs are collected, and livestock wearing bells around their necks are moved into pastures during the day, and back into paddocks at night. Wool is spun, clothing is woven, and grain is ground.

While trekking through these small hamlets, I thought back to the comfortable, material-goods filled life that I'd had the privilege to leave behind for the last month and a half. I couldn't help but notice that, although life is hard and cold for these mountain people, it seemed in many ways so much less complicated than mine. For that reason, a part of me yearned for such simplicity. I wondered what the woman who spends the morning collecting dung might be thinking about as she carries out her task. Questions about our society arose--have we exchanged a rhythmic existence, and a calmness and spaciousness of mind for multiple commitments, pressures of jobs and bills--albeit gaining a life of physical ease and comfort? How is our inner experience different when we flip a switch to turn on the heat, as opposed to if we were to go out into the woods to collect the firewood, carry it home, and build a fire?

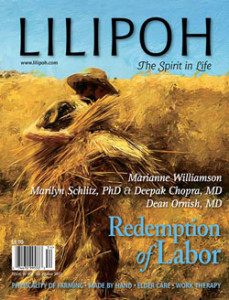

I, and many of the authors in this issue, postulate that in the Western world, there are core values we have lost along with our connection to labor. These include a sense of appreciation, integrity, value for both the material goods we have and need, and the resources required to produce them, and respect for what our bodies are capable of.

Can the ancient ways of the Tamang villagers inform our own modern choices? Reconnecting and becoming active participants in the labors of life has positive social impacts--working with our hands asks us to slow down, allowing us to interact with each other, to notice things, to consider, to care. Perhaps this issue of LILIPOH will get us all thinking of new ways to connect to and support the production of goods and services imbued with the qualities of simplicity, quality, rhythm, beauty, and sustainability. Share your ideas and insights with all of us! (editor@lilipoh.com)

-Christy Korrow, Editor of LILIPOH