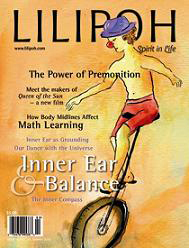

The Inner Ear as Grounding

By Nancy Mellon

By Nancy Mellon

Like the ancient Chinese and Indian Rishis before him, Rudolf Steiner saw the whole human form condensed within the human ear. In a lecture given in 1922, he described the tiny bony formations deep within the inner ear as a miniature person standing on an eardrum. The stapes or stirrup bone appeared to him as a version of the thighbone; the anvil he saw as a transformed kneecap, and the malleus as the lower part of the leg, its “foot” sensing the delicate vibrations of the drum of the ear much as the sole of your foot senses the ground. The curling cochlea bone deep within the inner ear he saw as a version of our intestines. “And so,” he said, “you can imagine, there inside the ear lies a human being, whose head is immersed in your own brain. Indeed, we bear within us a whole number of 'human beings', more or less metamorphosed, and this is one of them.”

Ears have fascinated me ever since I was a child. When I first learned about the bony components of the ear in school, I also was learning to play the piano. Our teacher’s name was Professor Drumm. Each time he would arrive with a loud rapping at the front door and it would seem as if the whole house gulped. The Professor had a shock of white hair and his face was always red. He boasted that his son could play every instrument in the orchestra and had perfect pitch but we never met this prodigy. My brothers did not like Prof. Drumm and seldom did what he asked them to do. Bang. He would slam the lid on the piano keys and there he would stand, ears red with musical rage as I inched into the room for my lesson, feeling the fume of his anger amidst shattered pencil points from the big noisy X’s in our assignment book where the job had not been done.

Though most of Professor Drumm’s musical selections were dismissed by my oldest brother Dann, one piano piece pleased him. “The Penny Whistle” was a sprightly little beginner’s duet for four hands. I remember my surprise when at last Dann learned to play his part with both hands. My second brother had wisely refused to practice the other part with him, so I learned it. One sunny summery afternoon, the metronome frolicking back and forth, our teacher would never know how the music took hold of us. We both took our places ceremoniously on the piano bench. Dann played his opening notes, and suddenly I felt inspired to stand up beside the piano and dance a little “Penny Whistle” jig. Then I rushed to sit down at my place and played my opening solo bit, while Dann got up and jigged. We played the remainder of the piece through without one mistake. Laughing triumphantly as we finished the last note, we both stood up and danced and hooted and whistled around the piano, before sitting down to play again. Together we had discovered bliss and harmony, the whole house dancing with happiness, no beginning and no end.

How do our listening ears inspire the sense of balance and movement, and open our souls to higher states? Steiner offered this explanation: “Rightly understood, our ears retain their membership in the spiritual world, while our limbs and torso walks erect in perfect balance entering the domain of gravity. We swim between two worlds. We can hear music with our ears and we can walk with our legs. We can choose to walk towards good deeds or bad deeds. Whichever way we choose to walk will resound. . . as either beautiful music or dissonant sounds.”

Opening the ears to careful listening is one of the primary tasks of teachers today. How can we inspire sensitivity so that the visual arts, poetry, music, and inner morality can resound within us. When I was teaching the third grade, the children were preparing to take up stringed instruments. Saint Patrick’s day was approaching as we practiced reciting “The Fiddler of Dooney,” a poem by the great Irish poet, William Butler Yeats. The children repeated the poem for days, elbows raised in violin bowing position as they swayed back and forth to feel the rhythm of each line.

. . . For the good are always the merry,

Save by an evil chance,

And the merry love the fiddle

And the merry love to dance:

And when the folk there spy me,

They will all come up to me,

With, “Here is the fiddler of Dooney!”

And dance like a wave of the sea.

Children often know what is good for them. Not unlike my brother and myself with our piano piece, one bright day the music of the poem came over them. First one child and then the whole class wanted to leap up on top of their desks to become bold and joyful fiddlers playing invisible fiddles. My intuition said “yes” to the children’s fervent desire to elevate their musical listening and speaking, while challenging their sense of balance. Careful active listening allowed each of the children to keep their balance perfectly as they moved to the lilting sway of the poem.

At the same time the children were discovering themselves as fiddlers, I too found some inspired new awareness. As soon as I saw it, how obvious it was. The whole violin resembles the structure of the human ear, from its sounding board to its two perfectly balanced scrolls at the top that elegantly mirror the coiled cochlea of our inner ears. With mathematically perfect pitch, they listen at the upper tip of the violin since the earliest inspirational days of Stradivari and Guarnieri violin-making, gyring there with curving mathematical flow. In the depths of the ears our cochleas, with similarly ingenious artistic service, harmonize and digest the sound currents that enter them, as part of the intricate, refined series of semaphore structures within the bones of the skull.

Deep within our inner ears, three semicircular canals bestow further gyroscopic support to the sense of balance. These semicircular canals are set at right angles to each other. Not quite complete semicircles, they are attached to each other within the inner ear, three-in-one. and connected to an empty cavity known as the vestibule. The canals contain hair cells bathed in fluid. Some of these cells are sensitive to gravity and acceleration and others respond to head positions and movement—side to side, up and down, or tilted. Posture and direction is registered by the relevant cells, and conveyed by nerve fibers to the brain.

The entire curving, fluidic landscape of the “intestinal” inner ear is encased in the hardest bone of the body. These dense temporal bones hold the deep fluid-filled hollows of the inner ears so that waves of sound, no matter how unfamiliar and varied, can be securely translated into the brain. We learn to enjoy their contribution to our well-being again and again within our whole being as we dance, sculpt, make music, or write ourselves into better balance. Our sense of harmony and relationship grow as we balance between our likes and dislikes, attractions and repugnance, our sense of color and musical composition, and all the thoughts and feelings that sway in and around us during the day, and in our dream life.

The complete description of the inner ear in Gray’s Anatomy reminds me of my mother. As my brothers and I were growing up noisily, her temporal bones were rock-steady. Yet she loved a wild and windy storm; she was at ease on the deck of a swaying boat in gusting wind. Being gifted with outstanding equilibrium allowed her to raise a large, resilient and honest family. No matter what was going on amongst us on land or water, she kept her ballast with a firm footing. Perhaps our whaler captain ancestor rose up within her to meet with exhilaration the daily pitch and groan of family life. When at different times my father and brothers and I experienced "seasickness" or "carsickness” or we children twirled to make ourselves dizzy on purpose, even if the room seemed to be reeling like a drunken sailor, our mother would be watching over us composed.

Like my mother, others today rely upon the powerful invisible plumb line descending from the inner ear. When the going gets rough, these firmly grounded folk maintain uprightness with a sure sense of gravity. "A sensory mismatch," a conflict between one cue and another, does not phase them for long as they hold their ground. Their gravity sensors in the inner ear may be at odds with what they are seeing. Pressure sensors in their feet may be telling them that the floor is tilted at an angle. Yet like cats and happy children they gracefully land well-balanced on their feet.

These days, of course, a conflict between vision and the sense of gravity is throwing many a brain into a state of confusion, resulting in lightheadedness, moral deafness, various degrees of nausea, and a woozy cacophony of as yet even undiagnosed diseases. The dizzying input of sound and movement on the road to school, electronic devices and lighting, computerized virtual spaces, and flashing external stimuli all contribute to a crippling sense of imbalance for young and old alike.

Yet well-tried antidotes abound. A sublime plumb-line and gyroscope hold us to earth; they are securely established there within our listening ears to right the world within us. In these increasingly dizzying times, may we choose with inspired inner equilibrium to hold on to this ancient listening post and rise up, like the children did to recite their poem. May we sway to surprisingly harmonious music. And may we seek to take hold of the refined instrument of our inner listening, to find within ourselves an ever more courageous, and resoundingly joyful sense of purpose.

Nancy Mellon teaches storytelling as a healing art widely in the USA and abroad. As a storyteller, writer, psychotherapist and teacher, Nancy Mellon supports family and community expression through the arts. The author of Storytelling with Children,and Storytelling and the Art of Imagination, her newest award-winning book, Body Eloquence, explores the healing resonance between physiology and story. www.healingstory.com