A Land of Soil, Milk and Honey

By Bernard Jarman

By Bernard Jarman

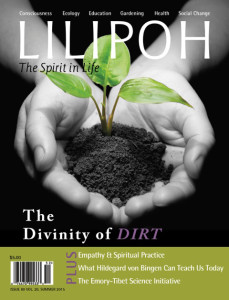

The soil and its fertility is the foundation for our existence and it is the soil of our planet which is above all under threat today. We know that the frequent application of mineral fertilizers and the use of chemicals destroys life in the soil and that the value of the food produced is thereby seriously diminished. Conversely, we also know that by feeding the soil in the right way and enhancing its vitality, abundant crops of health giving food can be produced. This is, at last, becoming more widely recognised with the designation of 2015 as the UN Year of the Soil. Creating soil and improving its fertility lies at the root of all true husbandry. Careful soil management, cultivation and compost making techniques are therefore essential and yet without the help of domestic animals the improvement of our soils would be a far longer proposition.

Soil is created in the first place through the activity of countless microorganisms and earthworms and especially the garden worm (Lumbricus terrestris). This species is noticeably active in the period immediately before and immediately after mid-winter. In December we find it (in the UK) drawing large numbers of autumn leaves down into the soil. Worms consume all kinds of plant material along with sand and mineral substances. In form and action, they live as pure digestive tract. The worm casts excreted from their bodies form the basis of a well-structured soil with an increased level of available plant nutrients (5% more nitrogen, 7% more phosphorous and 11% more potassium than the surrounding topsoil). They are permeated too by the vitality of the worm's metabolism. Worms also burrow to great depths and open up the soil for air and water to penetrate, increasing the scope of a fertile soil.

After the earthworm, the most important helper of the biodynamic farmer is undoubtedly the cow. The cow is a domesticated animal which has accompanied human beings for several thousand years and could be termed a co-creator of the European landscape. A cow's digestive system is designed to make use of roughage such as grass and hay. No creature has such a powerful metabolism as does a cow and on its journey through the organism the consumed plant material is thoroughly transformed and permeated with the vital forces of the animal's inner life. Cow manure is arguably the most effective and long lasting of all the fertilizing agents at the farmer's disposal and has been found to have a carry over effect of at least four years. It is also one of the most balanced. It is not only its manure however that makes the cow a valuable helper but also its ability to create rich and diverse pastureland. Cow and grass need to meet and interact with one another so that under the observant eye of the grazier, they can be productive and achieve what is best for animal, grass, and soil. A herd of cattle and particularly a dairy herd, is often experienced as being the very heart of the farm. This has a lot to do with the rhythmic care required—milking twice a day, the regular changing of pasture, seasonal work etc. This dedication is a kind of schooling for the farmer and also lays the foundation for a vibrant living community.

Along with cows, sheep, horses, and pigs also play significant roles within the biodynamic farm individuality. Sheep are very different to cows. Used to the open sky and ranging across wide open spaces, these animals also serve to enhance fertility but in quite another way. Where the cow enlivens the earth and makes it rich and fertile, the sheep brings lightness and balance. A pasture grazed lightly with sheep can start to blossom with herbs and clover while the bite of its teeth encourages the development of finer and shorter growth. Speaking of sheep during a biodynamic conference held in Botton Village during 1964, Karl König founder of the Camphill Movement, described them in relation to the elements as being “light in air.” "Their wool is woven through the powers of inner light," he said. This inner light is also gentleness and anyone who has worked with sheep will have experienced the heart warmth that seems to emanate from them, despite their seeming wish for constant flight. Perhaps this is why Christ is often described as the Lamb of God.

Pigs by contrast are different in their contribution to a farm's fertility. König describes them as expressing “fire in warmth.” They are beings of heat, have in most breeds virtually no hair on their bodies and are unable to sweat—a reason perhaps for their love of wallowing in mud. The heat burning within their organism might also explain why the manure they produce is so cold—it is only excreted once the warmth has been removed. Although it is cold and therefore slow to transform, the manure is rich in potassium and attractive to earth worms and its coolness beneficial on sandy soils. In earlier times, pigs were kept primarily for the fat they produce rather than the lean meat so much in favour today. Fat is stored energy and was made use of for candles and to provide warmth—bread and dripping was a farm staple for workers in the cold of winter. Pigs on a biodynamic farm serve to convert waste and especially high protein wastes such as dairy by products. They are cleansers of the farm and love rooting about in the earth. The soil they consume helps bring balance to their high protein diet while their activity stirs up and brings warmth and activity into the soil. The inner nature of pigs is also one of warmth and fire. They are enthusiastic—about their food, their surroundings and their visitors! The presence of happy pigs on a farm draws in the visitors.

Very different to the pig is the horse. The element of “sound in water” is how König characterises a horse—the sound is the music of movement. A horse is built for movement and outer muscular activity. Its place of origin is the endless open plain. Its movement creates a lot of warmth but instead of internalising it like the pig, this animal needs constantly to cool itself through sweating. Water moves through and perspires from the organism. The heat it generates is continually released. It is also excreted into the manure making it very warm and dry. This makes it ideal for creating hotbeds and for warming cold soils and compost. Its warmth increases soil activity and stimulates strong healthy plant growth. On their own horses are notoriously bad grazers but together with cattle can bring improvements to both the pasture and their own well being. Interest in using horses to cultivate the soil is gradually returning and experience shows it to be an excellent way of improving soil structure, reducing compaction and increasing vitality.

As well as the larger domestic mammals, farm poultry also play an important role. Like pigs, chickens have a connection to warmth and are constantly scratching around in the earth for grubs, roots and young shoots They bring air into the surface of the soil allowing it to breathe more easily while their rich droppings encourage rapid grass regeneration. Geese by contrast love to graze on the open field and associate well with sheep where they help reduce the number of parasites. They benefit in turn from the fresh young grass stimulated into growth by the grazing sheep. Ducks are citizens of the waterside and given access to a pond will keep water meadows (and gardens) clear of unwanted pests and parasites.

Although not directly involved in the building of soil fertility a farm may also have a cat and a dog. The cat has the task of keeping rodents at bay but it is also an animal that is familiar with every nook and cranny of the farmstead. Very little that goes on will pass unnoticed by the cat. The dog by contrast is a close companion of humans. Trained to herd sheep or guard the house a dog is the one who keeps communication lines open between the farmer and what goes on around. While the cat knows the place, the dog is interested in its master/mistress and in the comings and goings on the farm.

Finally we have the bees. Creatures of community and communicators of the sun. From their hives forager bees roam the countryside to collect nectar and pollen which they then transform in their hives through an intricate and powerful process of transformation using substances produced from their own bodies. As they harvest nectar from the flowers they release a fine aerosol of their venom which according to Steiner's investigations is essential for ensuring the continued vitality of flowering plants. They appear to hold the whole landscape in their consciousness as they fly from hive to flower and back again. Like earthworms, bees are also masters of metabolism and transformation but in an opposite way. Between them are the cows and the other farm livestock. They all contribute towards creating a fertile land of soil, milk, and honey. The farmer, like the conductor in an orchestra, is the one who guides and directs them so to become active assistants in the work of transforming and cultivating the earth.

References

König. K, Social Farming, Healing Humanity and the Earth, Floris Books, 2014

Osthaus. K-E, The Biodynamic Farm, Floris Books, 2010

Steiner. R, Bees

Reprinted with permission from Star and Furrow.